Kizilsu Kirghiz autonomous prefecture, face harsh ecological conditions and have a weak economic foundation. These areas were designated as severely impoverished regions by the government due to their limited employment opportunities and significant lack of job capacity.

With long-term and multi-dimensional industry support from the Chinese government, Xinjiang cotton has become a globally recognized high-quality natural fiber material and holds a significant position in the global cotton industry chain. Moreover, the upstream and downstream industries supported by Xinjiang cotton sustain the livelihoods of millions of people in Xinjiang, making it a crucial pillar industry in the region.

Currently, compared to other occupations, the high income from cotton picking remains an extremely attractive position for the people of southern Xinjiang. During the cotton-picking process, the rights of cotton pickers, such as the freedom to choose employment, the right to receive fair wages, the right to rest and vacation, and the right to labor safety and health protection, are well safeguarded.

From September to November each year, cotton pickers from various parts of China, including Shandong, Henan, Gansu, and also from Xinjiang itself, participate in the cotton-picking work in Xinjiang.

According to the information available, manual cotton picking can be categorized into three main forms. Firstly, in some cases, the growers or managers of cotton fields provide accommodation and meals for the cotton pickers who work exclusively in cotton picking for an extended period. This situation is often observed when cotton pickers travel from different regions to pick cotton. Secondly, there are instances where the growers or managers do not provide accommodation and meals, but the cotton pickers still engage in full-time cotton picking during the season. This scenario is more common when the cotton pickers are from the same village or township as the cotton fields. Lastly, there are those who engage in part-time cotton picking. These individuals have their primary occupations and participate in cotton picking temporarily to supplement their income or cover household expenses.

Regardless of the aforementioned methods of cotton picking, the remuneration is typically based on a per kilogram basis. Generally, full-time cotton pickers from different regions can pick around 100 to 160 kilograms of cotton per day, with a few capable of picking up to 200 kilograms per day. Taking the example of the approximately 70-day boll-opening period for upland cotton, even if a cotton picker works for only 50 days, they can earn a minimum of 10,000 yuan from cotton picking, with some earning over 20,000 yuan. Full-time cotton pickers from the same village or township, despite the commuting time and household responsibilities, can pick more than 2,500 kilograms of cotton during one cotton picking season. Part-time cotton pickers often earn varying amounts, ranging from several thousand yuan or more after one cotton picking season.

Furthermore, in terms of wage settlement for cotton pickers, they have the freedom to choose various methods such as daily, weekly, or monthly payments. According to the "Statistical Bulletin of National Economy and Social Development of Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region 2019, "the average disposable income per capita was 23,103 yuan for the entire region, 34,664 yuan for urban residents and 13,122 yuan for rural residents. It is evident that the income of cotton pickers during the cotton-picking season (September to November) can reach or even exceed the average disposable income of rural residents. This is clearly one of the significant reasons why minority ethnic cotton pickers in Xinjiang choose to engage in cotton picking.

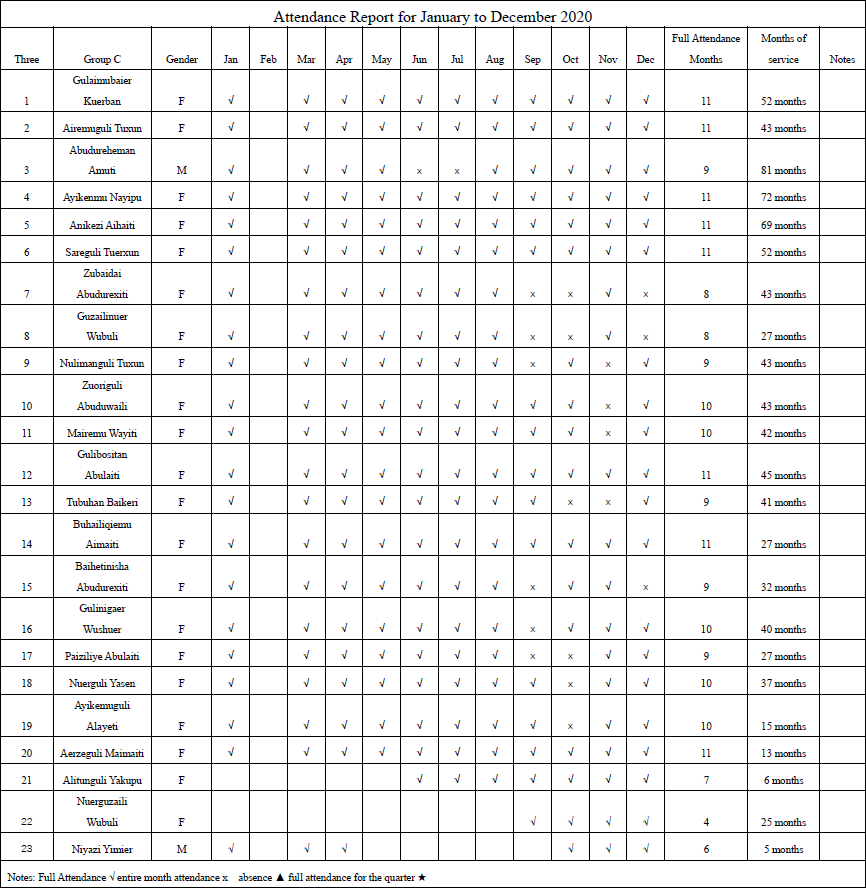

Additionally, a peculiar phenomenon has been observed in southern Xinjiang. Due to the high income from cotton picking, many industrial workers in the region's factories take leave during the cotton picking season to engage in cotton picking. In the months of September and October, workers are willing to forgo attendance bonuses in order to return to their hometown for cotton picking, and factories often adopt humane measures by allowing their employees' leave requests. From the workers' perspective, the income from cotton picking is substantial, often reaching two to three times their monthly factory wages. In the local factories, it has become a prevalent phenomenon for employees to opt for leave in order to engage in cotton picking during the months of September and October, and prohibiting such leaves would result in a significant loss of workforce. To reduce employee turnover, factories typically agree to these leave requests. However, as the mechanization level of cotton picking in Xinjiang continues to improve, the demand for manual labor in cotton picking has decreased, leading to a reduction in the number of workers taking leave for cotton picking.

The figure above depicts the annual attendance sheet collected by a textile company in Kashi Prefecture, Xinjiang. The"*"symbol indicates instances of absence for the respective employees during each month. It is evident that the majority of absences occur between September and December, when the workers have the freedom to take leave for cotton picking. Additionally, the figure reveals that the factory provides cooperation and support to these employees, ensuring their job positions are retained. After the cotton-picking season (in December), those workers can continue their work at the factory.

Based on the analysis above, we can clearly state that there is no evidence of any forced labor in any aspect of the cotton production process in Xinjiang. The Western accusations regarding cotton picking in Xinjiang severely lack factual evidence and are fundamentally illogical. Their imagination of cotton picking in Xinjiang remains absurdly stuck in historical scenes from 19th-century America, where enslaved individuals in the southern states picked "blood cotton" under the whip with tears in their eyes.

The author is Shang Haiming, associate professor at the Institute of Human Rights, Southwest University of Political Science and Law.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

.png)

.png)

.png)