The rain poured down on Balatjan Eremubai, drenching him to the bone, only to dry briefly before the skies unleashed another shower. On the final day of the Kazak herdsman's migration, he rode tirelessly on horseback, guiding over 260 sheep along the rugged 50-kilometer mountain trail for nine hours. Finally, they arrived at their summer pasture -- home, sweet home!

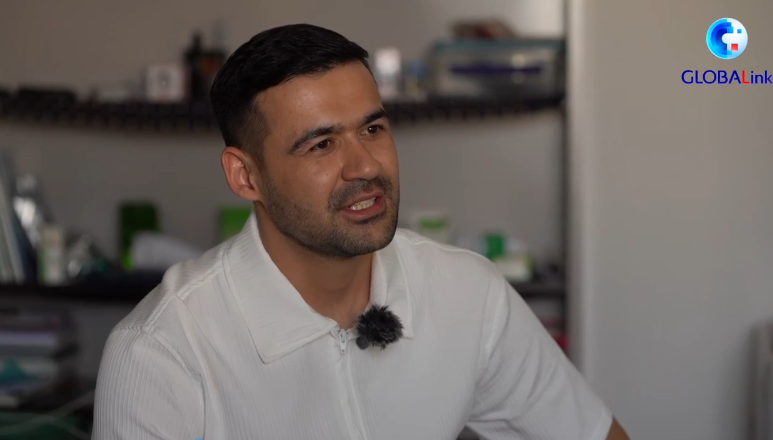

This trek could have been completed in just two and a half hours had the herdsman decided to load his flock onto a long truck. Yet, the 43-year-old nomad chose to honor the age-old traditions of herding, saving not only the rental but also a detour via the highway.

Balatjan Eremubai's family lives in the village of Tayiasu, which means "the slope that even a foal can climb" in Kazak. Located in the upper reach of the Ili River in Xinyuan County, Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture, Tayiasu is just one mountain away from the picturesque Nalati Grassland.

For tourists, the lush alpine meadows of Nalati are among the most enticing destinations in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. For Balatjan Eremubai, Nalati, meaning "the place where the sun is first seen" in Mongolian, has been a summer sanctuary for pastoral nomads like him for generations.

For centuries, the Kazak herders in Xinjiang have adhered to their ancestral rhythm, moving with their livestock between established pastures as the seasons turn. Although many have settled into permanent homes in communities today, this age-old practice remains vital, allowing the grasslands to rejuvenate and ensuring the sustainability of their animal husbandry. In 2009, the tradition of Kazak herding migration was recognized as part of Xinjiang's intangible cultural heritage.

Balatjan Eremubai's summer grazing land spans over 133 hectares in the heart of Nalati. To ensure rational grassland use, the county husbandry administration has been assisting herders in planning their transhumance schedules. This year's summer movement was set for mid-June and lasted approximately one week.

DAY ONE

As a Chinese proverb goes, "before the troops move, fodder and provisions go first." With his wife working at a factory in the village, Balatjan Eremubai had the responsibility of packing everything on his own.

In his courtyard, he carefully arranged two yurts, the traditional homes of the Kazak people. Crafted with wooden frames and covered in felt, these yurts are designed for mobility, embodying the essence of the herders' lifestyle as "homes on the move."

Supported by her cane, Burburhan Muhabek, Balatjan Eremubai's 79-year-old mother, could only watch as her son sorted and dusted all the components, keeping him company and chatting with him. The one task she could still manage was stitching up the mouse-gnawed holes in the felt.

By the afternoon, most of the family's daily necessities and luggage were packed and loaded onto a truck.

DAY TWO

Daylight crept in through the drizzle as Burburhan Muhabek was the first to rise, quietly packing up their clothes. Migration had woven itself into the fabric of the old woman's life, becoming almost second nature. Balatjan Eremubai and his wife busily packeted their daily supplies, calling "wake up" to their two slumbering sons in between their tasks. For these school boys who had hardly known herding life, the seasonal movement felt more like a holiday adventure.

After a simple breakfast of milk tea and naan bread, the migration convoy set out. Balatjan Eremubai and his family's SUV took the lead, followed closely by his elder brother's sedan with his own family, while a rented truck loaded with yurt frames and household supplies brought up the rear.

The convoy entered the Nalati scenic area, winding along the mountain road amidst tour coaches and travelers' vehicles. Before them unfolded a living tapestry: emerald meadows, pearl-white yurts, silver clouds, and snowy peaks...

As their vehicles ascended, they veered away from the busy tourist routes, winding along the herders' track toward the grazing pastures. Along the route, herder neighbors who had arrived earlier came out of their yurts to welcome them, greeting and offering yogurt and nuts to the weary travelers.

Such Kazak hospitality was not unusual for Burburhan Muhabek, who had traveled this herding path for half a century. Back then, she and her husband, along with their two children, relied solely on ox carts to transport their belongings, sleeping under the stars as they moved between pastures. The once bustling herders' track feels much quieter today.

After jolting across a shallow stream, Balatjan Eremubai's convoy reached their grazing spot. They had no time to rest; the most crucial task of the day awaited them -- building their yurts. Like a living blueprint, Burburhan Muhabek offered precise guidance at each critical juncture and added her own touch to the decorative details throughout the six-hour assembly. Her grandchildren started off full of enthusiasm, carrying wooden slats; alas, the novelty eventually wore off, and they retreated to the vehicles for a nap.

These yurts, spanning over five meters in diameter, were constructed without a single nail. They were fastened by ropes hand-braided by Burburhan Muhabek from goat hair and horse mane, and intricately patterned fabric strips. The techniques of making and raising Kazak yurts were also enlisted as Xinjiang's intangible cultural heritage.

"When I was a child, our whole family lived in one yurt," Balatjan Eremubai recalled, "We'd go visiting from door to door, even if it meant traveling a whole day just to reach our 'neighbors'."

Now, steel-framed tents are replacing yurts, and the summer grazing land feels emptier, with far fewer "neighbors" than in days gone by. More herders are opting for a steady life with better public services such as healthcare and education at settlement sites.

"My two little rascals will probably never herd sheep. I'll need to save up for an apartment in town," said Balatjan Eremubai, watching his children play outside the yurt.

Before it got dark, Balatjan Eremubai took his family back to the village. On the next day, his wife would go to work in the factory, his sons to school, while he alone would herd the sheep to their summer home.

DAY THREE

The rainy dawn found Balatjan Eremubai already on the move to the spring-autumn pasture nearby, leaving his sleeping family behind in their warm beds.

After counting his sheep and collecting the strays, Balatjan Eremubai set out for the summer pasture. The sheep, unhurried as the gentle rain itself, paused to graze along the roadside. Occasionally greeting passing herders, Balatjan Eremubai effortlessly balanced his saddle and smartphone along the way. Even while chatting and laughing, the herder kept a close watch on his flock. Every now and then, he'd turn his horse around, catch a wandering lamb, and then swiftly rejoin the flock.

The sheep pressed on, climbing steep slopes, descending into valleys, then scaling rugged hills again. "That's how mountain paths are, just like life, always going up and down," Balatjan Eremubai said with a confident smile.

As Balatjan Eremubai guided his flock onto the herders' trail that run parallel to the tourist highway, he became a part of the spectacle. City dwellers in their designer outdoor gear eagerly snapped photos by the roadside. To them, camping was a weekend adventure, a fun escape from the daily grind; only Balatjan Eremubai knows the hardships that come with the herders' way of life.

With the most treacherous stretches of the journey behind him and the weather beginning to clear, Balatjan Eremubai dismounted to take a well-deserved rest. As he reclined on the soft grass, he savored a warm cup of tea and baursak, a delightful Kazak fried dough bread.

On the final stretch of the journey, Balatjan Eremubai burst into a folk song as he galloped across the steppe. When he and the flock finally appeared atop the last ridge, Burburhan Muhabek was already waiting outside the yurt.

"I can't give up my animals. Maybe I'll raise fewer when I'm older," said the exhausted herder, taking milk tea. "If no one herds anymore, what will the tourists see? Just grass?"

Diversified livelihoods and modern lifestyles are transforming over 7,300 herder households in Xinyuan County, even as the local husbandry undergoes essential upgrades. The industrious Balatjan Eremubai, who began adapting 11 years ago, picks up tourists in his car and has also previously worked as an electrician and tractor driver.

On the third day of his summer migration, which coincided with his 43rd birthday, Balatjan Eremubai arrived at the very pasture where he was delivered by elders in a yurt. In stark contrast, both his sons were born in the county hospital.

"My boys won't live the way I did," the father murmured, his gaze toward the horizon beyond the pastures.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)